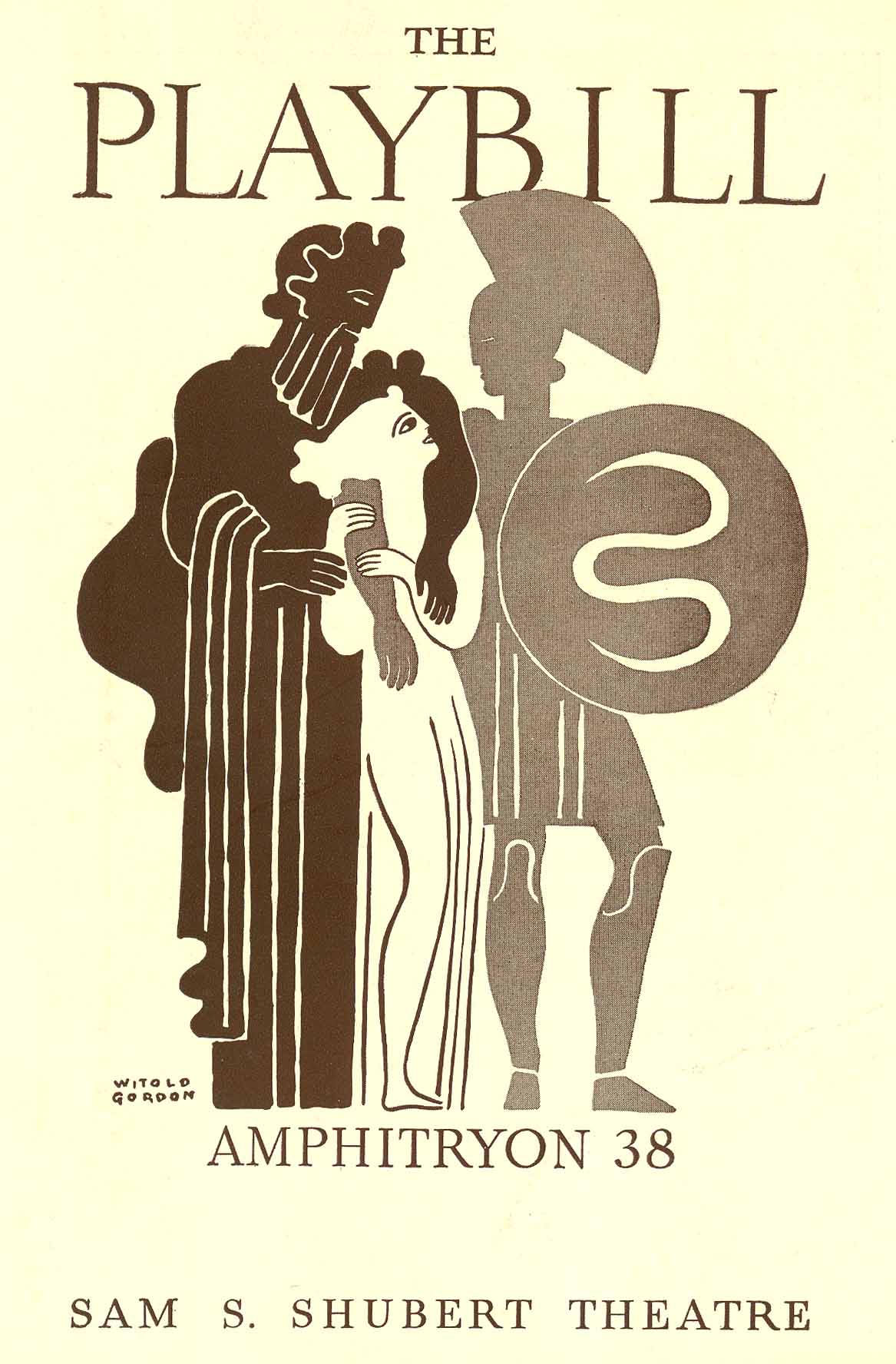

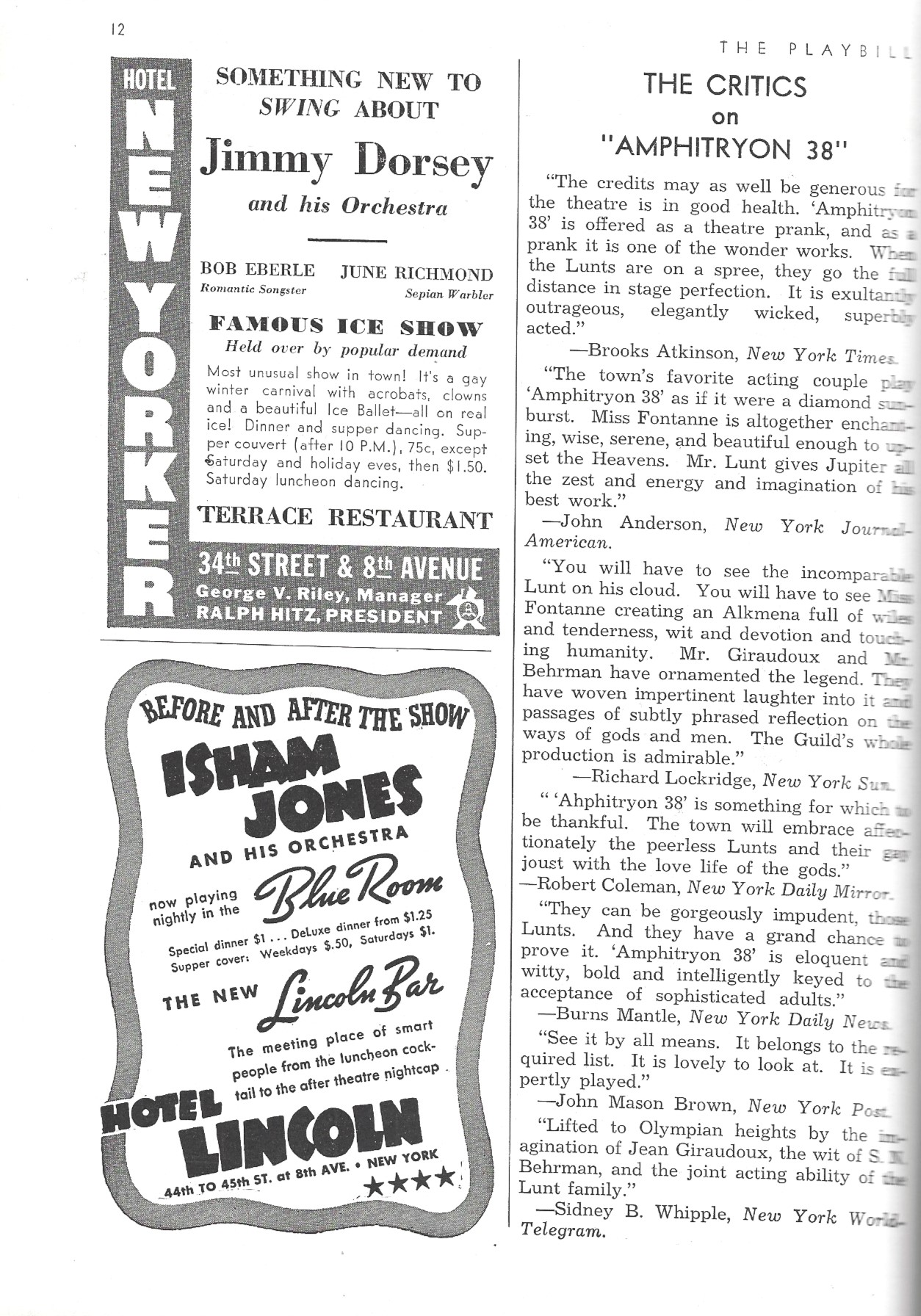

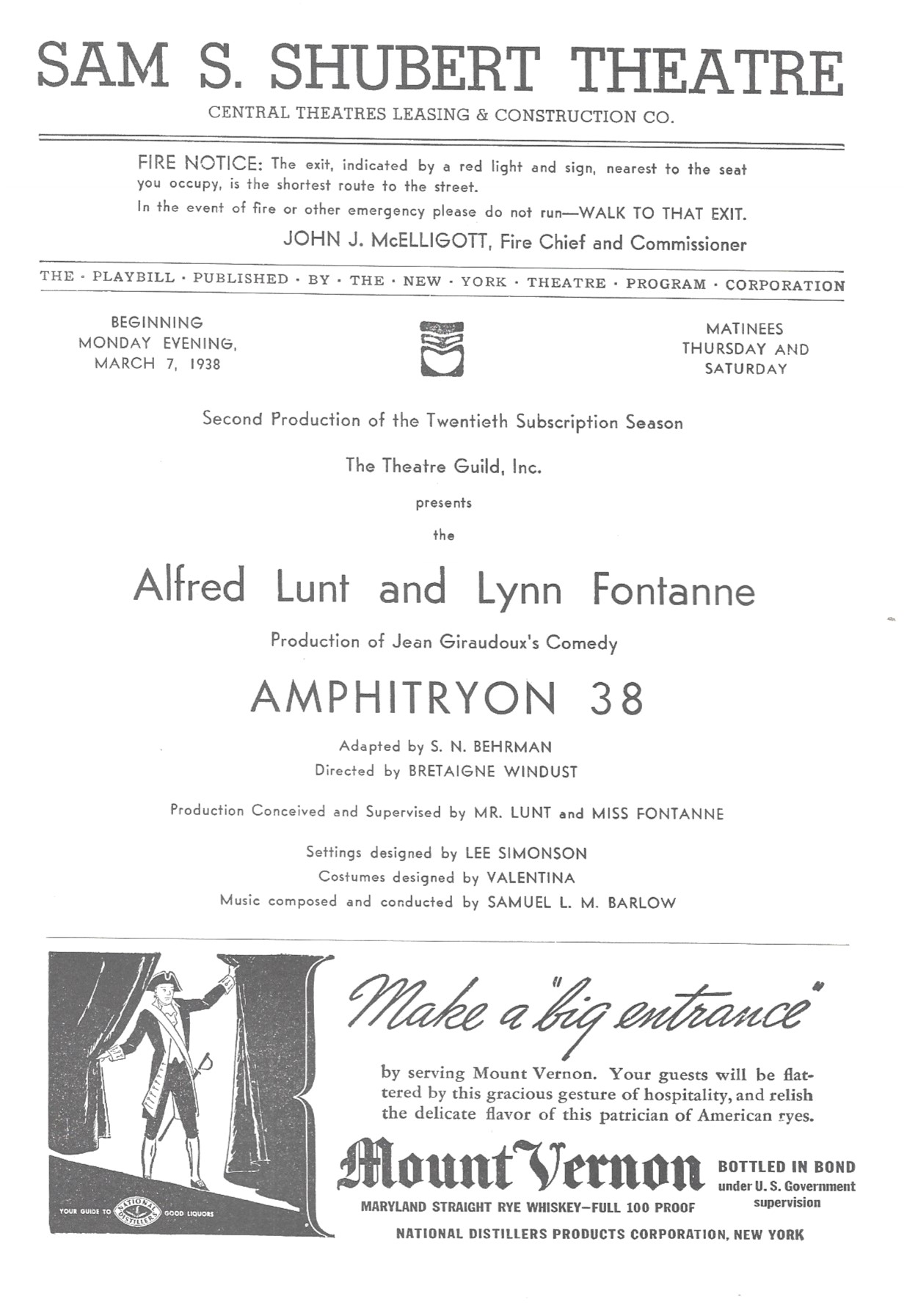

Amphitryon 38

Sam S. Shubert Theatre / NYC / March 7, 1938

![]()

(starring Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne / 153 performances)

Amphitryon 38 November 1, 1937 - March 1938 at the Sam S. Shubert Theatre.

from Time Magazine:

- Monday, November 8, 1937 -

With a whinnying of trumpets and a rolling rataplan of drums, the curtains at Manhattan's Shubert Theatre parted this week

to disclose two apparently naked gods reclining on a cloud, their bare bottoms perked toward the heavens, their amorous gaze fixed

on the somewhat startled audience. The bare bottoms were moulded of impersonal papier-mache, but the silver-bearded Jovian head on

the left was unmistakably that of Alfred Lunt. Theatre Guild subscribers, present for the Manhattan opening of Amphitryon 38,

settled back expectantly in their seats. They realized that Jupiter Lunt's eyes were not feasting on them but on the earthly abode

of Alcmena Fontanne. And they expected that in the next hour or so something deliciously scandalous would come of it.

Even those who did not know the legend of Amphitryon*—whose wife Alcmena was seduced by Jupiter—expected this because they knew Alfred Lunt

and Lynn Fontanne. Spirited Aphrodisiantics, urbanely conducted infidelities are the hallmark of Lunt-Fontanne plays, which take on added zest

from the well-known fact that Actors Lunt and Fontanne have been contentedly married for the last 15 years.

The Play. Amphitryon 38, adapted for the Lunts by Samuel Nathaniel Behrman from the French farce of Jean Hippolyte Giraudoux, is

approximately the 38th dramatic version of the Theban legend of how all-powerful Zeus (Roman Jupiter) had to assume the mental as well as the

physical aspects of Amphitryon before Alcmena would bed him. The Lunts studied the play, which they were quick to see contained one of their

favorite situations, for several months before trying it out last June in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Later they took it to Baltimore,

Washington and Cleveland, to whose critics the play seemed 'mellow . . . exhilarating . . . sparkling . . . sagacious.' To provincial

Lunt-Fontanne fans, Amphitryon 38 was pretty much what the doctor ordered. Broadway was not surprised when Amphitryon 38 rode into

Manhattan to find first-nighters willing to pay as high as $100 for a pair of seats.

What first-nighters found they had paid for was a comedy written with a stylish stylus, a mort of Jovian musing, some heavy-handed Olympian

plotting—and the Lunts. Just as all but the extremely myopic soon discovered that the display of buttockry in the startling opening set was a

plaster hoax, so none but the most zealous Lunt-Fontanne champions found Amphitryon 38 the perfect play.

Featherlight, the tale gets going when Jupiter's bang-crash arrival on earth— he forgot the law of gravitation—brings it home to him that assuming

human simplicity is going to be a very complicated process. To gain Alcmena he has to sacrifice his wistful whim to be loved for himself alone.

Husbandly attention Alcmena welcomes, lover's desire she abhors. "Desire is a half-god," she affirms. 'Let's leave the half-gods to the adolescent girls

and the casually married.' In the battle of wits and wills between the omnipotent god and the constant matron, Jupiter is charmed into a distinct loss

of dignity and self-esteem as the price of his stolen night.

The Behrman adaptation makes a noteworthy effort to retain the sparkle of the original French sallies, tries to bring the ancient story into

focus for modern audiences. Omniscient Jupiter, for example, finds himself misquoting from the as-yet-unwritten Hamlet ('Nymph, in thy orisons,

be all thy sins remembered') and he offers Alcmena a glimpse into the future at the 'eleven great beings who will constitute the finest ornament in

all history — one with his lovely Jewish face; another with her little nose from Lorraine.'

Box-office appeal of the Behrman adaptation of the Giraudoux Amphitryon is that the Olympians behave like contemporary Parisians.

Mercury (Richard Whorf) tries to make a little time for himself while carrying a message to Alcmena from his boss. Alcmena suspects

that Jupiter has perhaps been playing a deeper game with her than she knows: 'Are you sure that you've never been my lover? Because

my knowledge of men leads me to believe that when they're as noble as this, it's because they're already satisfied.' Jupiter Lunt,

however, considers the play a 'romance of fidelity' that in less careful hands might have become a bedroom farce.

Lunt & Fontanne 21. The two most theatrical people on the U. S. stage are of nontheatrical parentage. Molasses-voiced Miss Fontanne is the

English-born daughter of a French type-founder, broad-shouldered Mr. Lunt the son of a Wisconsin timber man. They came to the stage in picturesque

ways. In the early 1900s, a friend of the Fontannes brought little Lynn to Ellen Terry in London, had the child recite Mme Terry's favorite scene,

a Portia speech. Impressed, Mme Terry agreed to sponsor the girl, took her on tour, gave her a role in Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire (1905). A walk-on

part was her first London appearance, and 1910 first brought her to the U. S. to play in Mr. Preedy and the Countess.

Alfred Lunt had sipped the heady wine of amateur dramatics in Carroll College (Waukesha, Wis.), with an impersonation of Harry Lauder. In 1913 he

went east to Harvard, found his way into John Craig's Castle Square Stock company in Boston. He got $5 a week, furnished his own costumes from

Salvation Army castoffs. A plethora of old-man parts discouraged him, and next year he went back to his Wisconsin home, Genesee Depot. Two days

after he got home came a beckoning telegram from Margaret Anglin. He joined her in Chicago, played 18 months on tour in plays ranging from

Beverley's Balance to Iphigenia in Tauris. Fading Lily Langtry then acquired him for her vaudeville sketch Ashes, giving

him the most juvenile role of his career. Roadshow roles opposite Laura Hope Crews and another turn with Margaret Anglin brought him to Manhattan

in 1917, the same year that Laurette Taylor's company came in off the road, bringing Lynn Fontanne also to Manhattan.

But it was not until two years later that they met, on a staircase backstage in Manhattan's Hudson Theatre, where they were

both rehearsing for Maid of Money. That was the first of the 21 plays in which they have since appeared together. At their

meeting courtly Alfred Lunt bent to kiss Miss Fontanne's hand, flopped down the staircase. The play tried out in Washington,

flopped too. The romance was more durable. They remained in Washington with George C. Tyler's company, played there in A Young Man's Fancy,

and parted, Miss Fontanne to Chicago with the company, Mr. Lunt to rehearse for Clarence, which Booth Tarkington had written for him.

Their golden year was 1921. She had her first great success then, in the George S. Kaufman-Marc Connelly Dulcy. And Actor Lunt,

after a two-season run with Clarence, was established on Broadway. Next year they were married.

Their first play on Broadway together was Sweet Nell of Old Drury, a salaryless Actors Equity benefit.

Actor Lunt recalls it as his wife's first part as a beauty, in the role of Lady Castlemaine, remembers that they spent

all their ready cash on fake jewelry to make her look more fetching. The acclaim for the new stage beauty was led by Mr. Lunt's

deaf mother, Mrs. Harriet Sederholm, whose untempered voice could be heard quite plainly from the audience asking her neighbor,

'Isn't she a dream?'

In 1924 the Theatre Guild decided to produce Ferenc Molnar's The Guardsman. Its chief characters were a married actor

and actress, its theme a test of fidelity. The Guild's canny Theresa Helburn saw the piquant possibilities of casting a happily-married

stage couple in the parts. The tremendous success of The Guardsman led to 14 more such pairings. The Lunts are now known

throughout the U. S. as the leading Mr. and Mrs. of the theatre.

Broadway perennially bemoans the collapse of the road. For the Lunts the road has never failed. Since The Guardsman

they have, in Alfred Lunt's phrase, gone buckety-buckety over the U. S., always sure of a hearty welcome from coast to coast.

The Lunts put this success down to a variety of good plays. The nation puts it down to the bickering, wrestling, fighting, cooing,

unfailingly endearing intimacy of Lunt-Fontanne on-stage relations, their expert charm. The Guild paired them in Arms and the Man,

The Goat Song, At Mrs. Beam's, Pygmalion, Juarez and Maximilian. In 1927 they did The Brothers Karamazov, The Second Man,

The Doctor's Dilemma together, and in 1928 Actress Fontanne opened Strange Interlude on Broadway and Actor Lunt played

Marco Millions and Volpone. Since then they have not been separated. They played Caprice in Manhattan and London, returned to

Manhattan for Meteor, did Maxwell Anderson's turgid Elizabeth the Queen, then swung into the highly successful

Reunion in Vienna. Following the road tour of Reunion in Vienna, the Lunts parted for a time from the Theatre Guild.

Eternal Triangle, Inc. The underlying reason for their separation from the Guild went back to the days before their marriage, days spent

in theatrical boarding houses in Broadway's gingerbread side streets, planning for the future with their bright young friend, Noel Coward.

Coward recalled those days this year in his autobiography, Present Indicative: how, over delicatessen potato salad, they plotted their

future eminence. Lynn and Alfred were to marry, were to become an idolized pair of the theatre, were to act exclusively together. Coward was to proceed

in his many-faceted brilliancies, and when all three were firmly and separately established in fame, they were to "meet and act triumphantly together."

By 1933 their triangular dream had been realized in Coward's Design for Living, "a flicker of ecstasy sandwiched between

yesterday and tomorrow which flounced its polyandric way into theatregoers' favor. The Lunts were at their supreme best with Coward's

neo-Epicurean, gauzy dialogue, his gaily immoral situations. It was a reunion that merited continuation, got it in the businesslike

form of Transatlantic Presentations, Inc. When the Lunts returned to the Guild for The Taming of the Shrew in 1935, the 1936

Pulitzer Prizewinner, Idiot's Delight, and Amphitryon 38, it was not as a happy-go-lucky couple, but as part of this

corporate body. Founders, stockholders and officers are the Lunts, Coward and Producer John C. Wilson. No matter who is working,

all make money. Wilson was associated, with Max Gordon, in the production of Design for Living, and later in Point Valaine,

the second and not so successful play Coward wrote for the Lunts. The incorporation made Coward and Wilson profit-sharers in the Lunts'

plays for the Theatre Guild, let the Lunts in on profits from Wilson's Excursion and George and Margaret, from Coward's Tonight at 8:30,

and from productions by both abroad.

Matters like these, Miss Fontanne, now turning 50, has learned to leave to her husband, six years her junior. On stage or in the

tense atmosphere of a first night she is stability itself, rich-voiced, self-assured, in full emotional control. But Lunt sometimes

calls her Rich Lynnie because of her Lady Bountiful complex, says she grieved for months in 1930 because an acquaintance of theirs

had lost heavily in the market crash . She wanted to make him a pensioner. It is Lunt who insisted on the clauses in their Theatre Guild

contract stipulating that they be cast together whenever they are on the road, that scripts calling for their appearance in Manhattan

separately must be acceptable to them. Since 1928 they have not accepted any.

When Alfred Lunt is asked why he prefers the stage to the cinema, he shrugs, retorts, 'Why do you like potatoes?' In point of fact, the

flavor of the typical Lunt-Fontanne play is a little too gamy for the Hays-censored cinema. Once, however, they took a play before the camera,

The Guardsman (1931). Since then Hollywood has produced purified versions of their more lusty successes, Noel Coward's Design for Living,

Robert Emmet Sherwood's Reunion in Vienna — but not the Lunts.

Whether or not the Lunts would be good for Hollywood, Hollywood would probably not be very enjoyable for Alfred Lunt. He and his wife

are theatre people through & through. Alfred Lunt has worked 30 to 40 weeks a year for 23 years in the theatre, but fears first nights

as the devil fears holy water, worries over the size of the audience, suffers tearful agonies if there is a hint that his performance

has not been up to his best. One of the consequent duties of faithful, bustling Lawrence Farrell, once his dresser, now his play manager,

is to beguile Lunt out of these funks. Farrell bounces in between acts with box-office reports, fanciful tales of extra chairs required in

the balcony. Applause is Lunt's meat, disapproval his poison. During Reunion in Vienna in London he was making a curtain speech when some

one called 'Louder!' Lunt thought the man said 'Lousy!' and was ready to quit the stage and go back to farming in Genesee Depot.

At Genesee Depot the Lunts live in a converted chicken house during their vacations, raise choice broccoli, cantaloupe, a wide variety of herbs,

vegetables and flowers, swim in the swimming pool that Design for Living paid for, pamper their dachshunds Elsa and Rudolf, indulge in

fancy cookery, their mutual hobby. It is the same farm, lovingly elaborated, where Alfred lived as a boy. Natives still call him Bill, a nickname

he got from worshipping a boyhood hero, Buffalo Bill.

Whether in town or country the Lunts are always actors. Candid camera shots of them in the fields invariably look posed; caught caressing

Elsa and Rudolf, they resemble the dog fanciers in the rotogravure sections. Acting is a large part of their life, and their life is a

most important part of their acting. Working on a new play, they learn the lines by rote, rehearse interminably around the house. They

work out scenes, time lines, until the author's conception, blended with some dash of Lunt-Fontanne sauce, is brought to a satisfactory

simmer. For the audience the result looks like naturalness done to a turn. That this naturalness is frequently naughty is half the charm

of Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. The other half is the reassuring fact which enables even the Old Lady from Dubuque to giggle at them with

a clear conscience. For as one such old lady is reported to have said: 'Isn't it comforting to know they're married."

*Presumably to simplify matters for a nonclassical audience, half the cast of Amphitryon, 38, has Greek names, Half-Roman,

while Guild programs listed Alcmena as Alkmena, a simplified version of neither."

CLIPPINGS

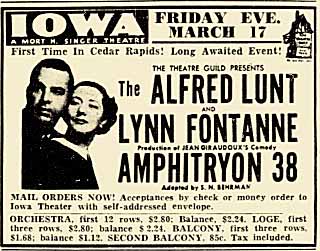

- Cedar Rapids, Iowa / Sunday; March 5, 1939 (pg.20) -

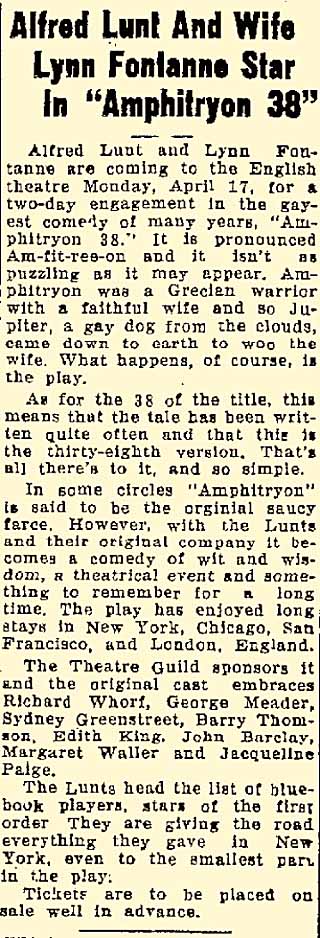

- Logansport Press / Logansport, Indiana / Sunday; April 9, 1939 (pg.9) -

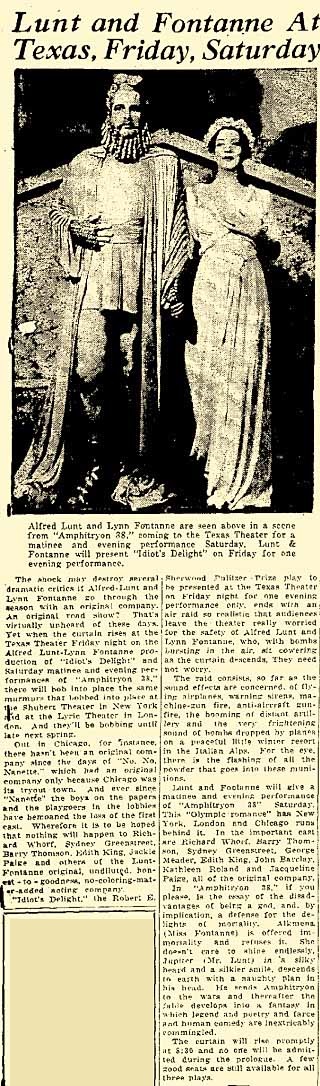

- Winnipeg Tribune,/ Winnipeg, Manitoba / Sat, May 28, 1938 (pg.41) - San Antonio Express / San Antonio, Texas / Sunday; February; 12, 1939 (pg.29) -

Return to Broadway Page