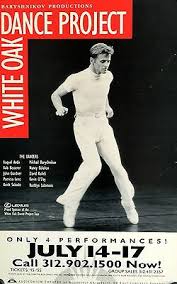

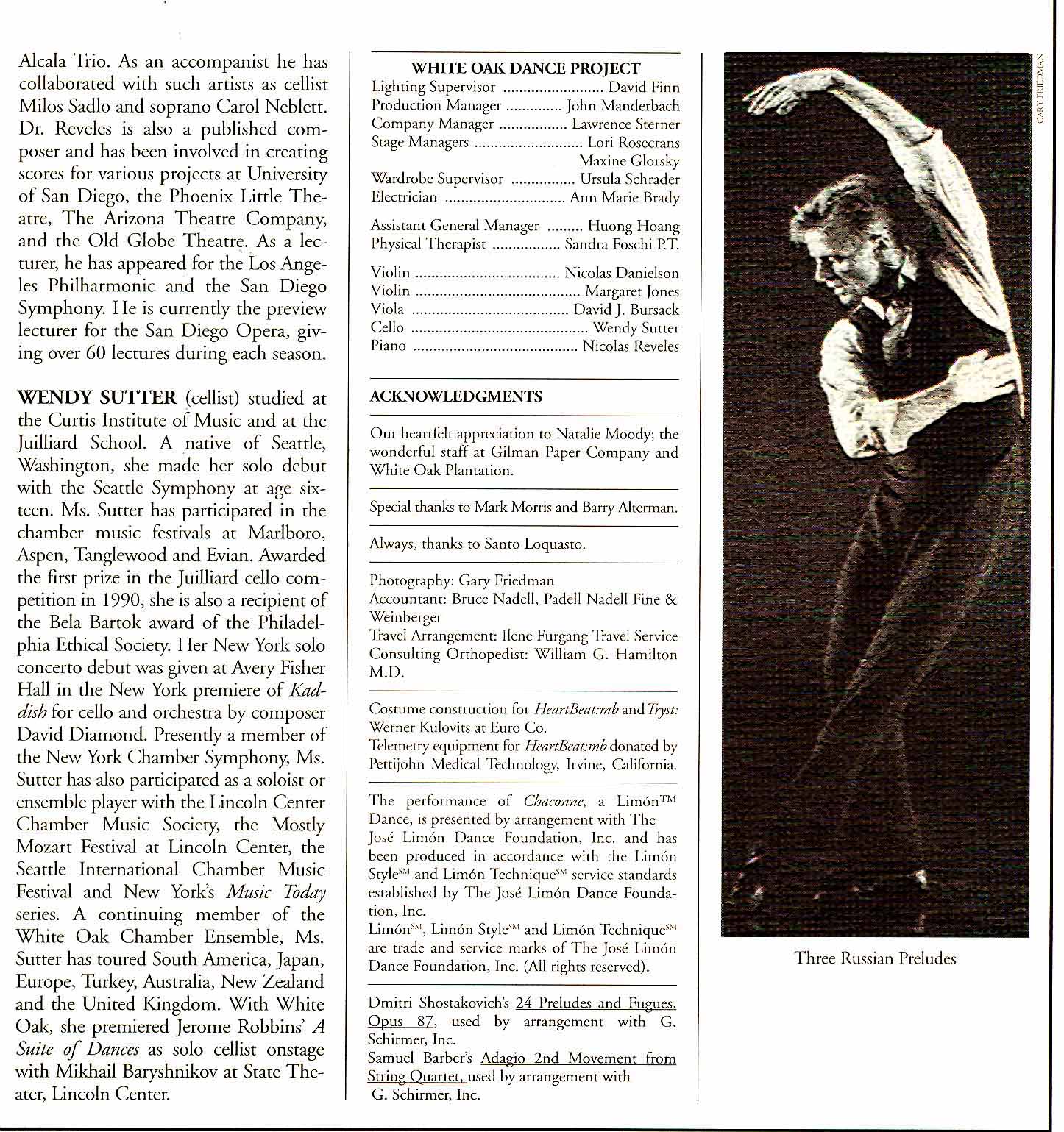

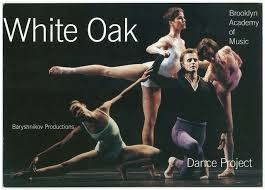

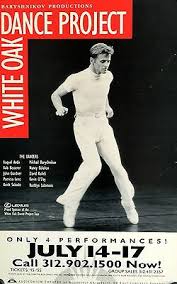

White Oak Dance Project / February 7, 1998

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) / Wiltern Theatre

- ALSO -

LA Times: DANCE; Baryshnikov & Co.: 'We Don't Do Ballet'

by Terry Trucco / February 27, 1994 / Section 2, Page 1

- AND -

Christian Science Monitor Review / June 5, 1995

from Wikipedia:

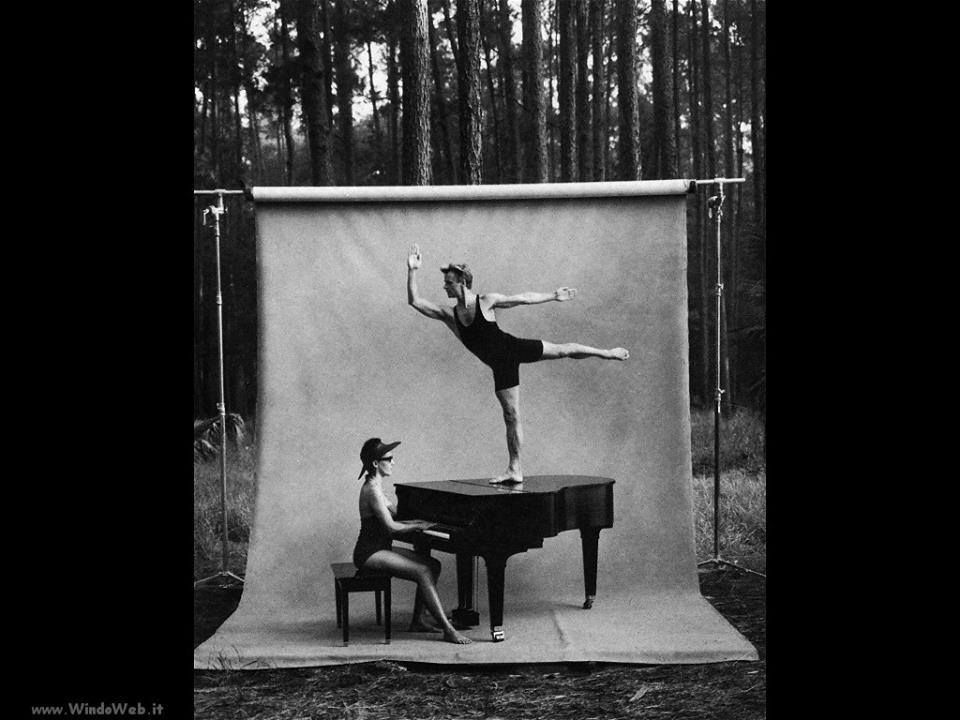

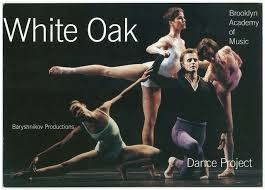

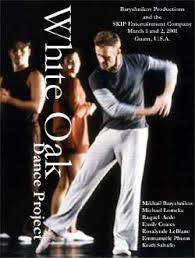

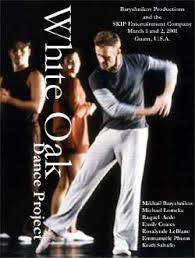

The White Oak Dance Project was a dance company founded in 1990 by Mikhail Baryshnikov and Mark Morris to be the touring arm of the Baryshnikov Dance Foundation.

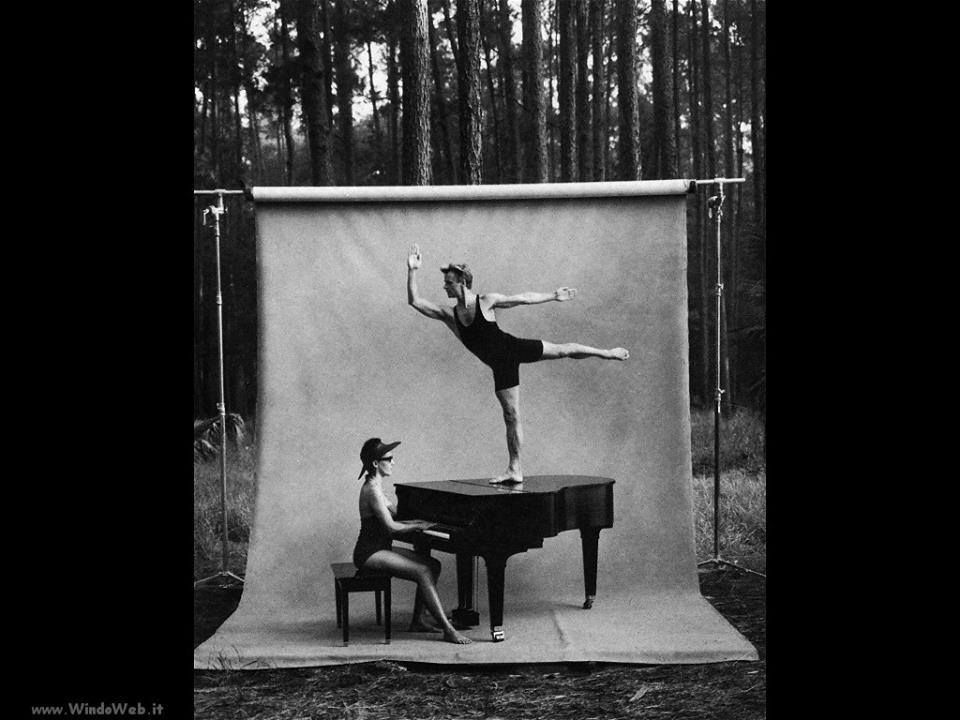

The company took the name of the animal preservation and land plantation made famous by dance supporter Howard Gillman, who built dance studios on his White Oak Plantation

near Jacksonville, Florida for the company to create its first tour. The studios quickly became the premier location to workshop works being created by many of the world’s

leading choreographers.

The company continued to tour until 2002, allowing the Foundation to concentrate on the 2004 opening of the Baryshnikov Arts Center in Manhattan. The company featured alumni

of major dance companies and commissioned new pieces from Morris, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, Jerome Robbins, David Gordon and others.

>

LA Times: DANCE; Baryshnikov & Co.: 'We Don't Do Ballet'

by Terry Trucco / February 27, 1994 / Section 2, Page 1

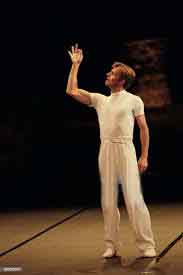

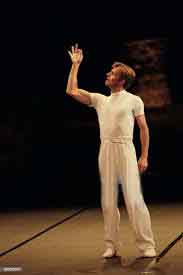

THE SCENE, IN MANY WAYS, WAS familiar. On a recent blustery afternoon, Mikhail Baryshnikov, the preeminent male dancer of his time,

stood in a near-empty Manhattan studio, rehearsing a new dance by Jerome Robbins, the third Mr. Robbins has choreographed for him

over the years. In black tights and a blue T-shirt, with his boyish shock of sandy hair, Mr. Baryshnikov cut a lean, sculpted figure.

But this is 1994, 20 years since he left Russia's Kirov Ballet to dance in the West, 8 years since he last performed "Giselle," 4

years since he started the White Oak Dance Project, his modern-dance troupe.

And like the steps, the patter had changed. "This iswhere I feel so sorry for myself, for my knee, for my age," Mr. Baryshnikov said

wryly, holding an arabesque as a cellist played a mournful saraband from Bach's Suites for Solo Cello. The musician switched to a gigue.

Mr. Baryshnikov responded, marking the first few bars, then breaking into a jazzy romp. After a somersault, he essayed an immaculate

string of turns, a reminder of his greatness in major classical ballet roles. "You've got ballet steps in there," teased Rob Besserer,

a charter member of White Oak. Mr. Baryshnikov punched him playfully. "We don't do ballet," he replied.

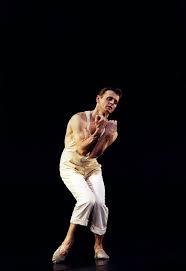

Ask Mr. Baryshnikov to describe the type of work he performs these days, and he says, "It's dance, just dance." In the last few years,

he has redefined himself as a dancer, abandoning the classical roles that made him famous and trying on a variety of modern styles.

In New York, audiences could follow his progress through guest appearances with modern-dance troupes like those of Paul Taylor,

Martha Graham and Mark Morris.

But the best indicator of his current course is his White Oak Dance Project, where he chooses what he dances and who dances with him.

After four years -- and visits to more than 90 cities around the world -- Mr. Baryshnikov's troupe will dance in Manhattan for the

first time, with six performances at the New York State Theater, beginning on Tuesday.

The best things to do in N.Y.C. during the hottest season of the year.

This limited-edition newsletter will launch before Memorial Day and run through Labor Day.

White Oak's premise is simple but unusual. Most modern-dance companies devote themselves to the work of one choreographer. White Oak,

by contrast, was conceived as a group where dancers with long and varied careers would perform works by a variety of modern choreographers,

"people we like and admire," says Mr. Baryshnikov, who is 46 years old. The group seeks a mix of the old and the new. Besides new commissions

by Mr. Robbins and Joachim Schlomer, a 31-year-old German choreographer, the State Theater season includes works by Merce Cunningham,

Hanya Holm, Mark Morris, Twyla Tharp and Kevin O'Day, a company member.

Why did it take so long for White Oak to play New York? A combination of reasons, Mr. Baryshnikov concedes, from his personal desire to

sidestep what he views as an unsympathetic New York dance environment, with its "politics and policies," as he puts it, to the not

inconsiderable cost of a New York season -- in this case, close to $500,000.

Reviews have generally been favorable in major cities, from San Francisco to Sao Paulo, with some exceptions, like Paris. White Oak's

return visit to London last year was more warmly received than its first, with Mary Clarke of The Guardian describing the company as

"infinitely stronger and better."

The troupe has also evolved in its four years, shrinking from 14 dancers to 8 -- including Mr. Baryshnikov -- a size he believes is a

perfect fit with the chamber quintet that plays at each performance.

"I think this past year we started to feel we had something that was solid and good," says Kate Johnson, one of White Oak's original members.

"Misha agonized quite a while about whether to go through with a New York season. But he decided we have to do it, then see how the group

feels after that." Though the troupe has bookings through the end of the year, Mr. Baryshnikov says White Oak won't go on forever.

"It could end next season," he says.

"The high pressure of New York is like a crucible," Ms. Johnson adds. "We will either go up in smoke or come up covered in gold."

A few days later, in a Lincoln Center coffee shop, Mr. Baryshnikov seems oblivious to the stir he's causing as a post-matinee crowd from

New York City Ballet files in. He dutifully signs an autograph for a woman who gazes at him adoringly, then returns to his chili and the

conversation. When he warms to a topic, he is charming and engaging. "I loved Erick Hawkins's new dance 'Many Thanks,' " Mr. Baryshnikov says.

On the lookout for works for his company, he says he sees as much dance as he can, mostly modern.

Let the questions veer toward things he'd rather not talk about, however, and he becomes icy and withdrawn. He declines to discuss his tenure

as artistic director of American Ballet Theater, a post he resigned abruptly in 1989 after a bitter dispute with the company's management and

board over financial and personnel issues. "I haven't seen anything they've done since I left," he says. "I've never been in town at the same

time they were performing."

His preferred subject these days is, of course, White Oak, where he has surrounded himself with a notable collection of experienced modern dancers.

Ranging in age from 30 to 47, they include Lar Lubovitch alumuni Nancy Colahan and Mr. Besserer, the former Paul Taylor dancer Ms. Johnson,

Ruthlyn V. Salomons from Donald Byrd/The Group, the former American Ballet Theater soloist John Gardner, Patricia Lent, a nine-year Merce Cunningham

veteran, and Mr. O'Day, who has danced with the Joffrey Ballet and the Frankfurt Ballet. (Mr. Baryshnikov dances at every performance but not in

every work.)

But Mr. Baryshnikov considers mature dancers an asset. "They're a bit more complex and relaxed at the same time," he says. "They

have their careers in their pockets and don't have anything to lose or prove. They know how to learn a new piece in the most

productive way. And we don't have to deal with ego problems."

The eclectic backgrounds of the White Oak dancers have proved advantageous as the troupe tackles works by different choreographers.

"In class, we're always watching each other," Mr. Baryshnikov says. "When we worked on Paul Taylor's piece, we watched how Kate was

working." For "Signals," a 1970 work Merce Cunningham suggested when Mr. Baryshnikov requested a piece for White Oak's New York debut,

the dancers watch Ms. Lent.

Yet, while performing in so many diverse styles distinguishes the group, Ms. Johnson admits it may also be a shortcoming. "We're working to learn

the distinctive language of each choreographer," she says. "We don't want to be a museum. But we don't want to be the Muzak of modern dance, either."

In some ways, learning works by choreographers like Graham, Taylor and Cunningham -- the modern moderns, as Mr. Baryshnikov calls them -- has been

toughest for White Oak's most prominent member. The modern-dance choreographer Paul Taylor believes that it's harder for a trained ballet dancer to

learn another form. "There's the double job of learning something new and unlearning something ingrained," Mr. Taylor says. Nonetheless, he has high

praise for Mr. Baryshnikov's diligent efforts in a solo he danced with the Taylor company last year. "But I don't know if the experience of performing

it was entirely fun for him," he says.

Whether or not the role was fun -- Mr. Baryshnikov admits it left him sore for a month -- hardly seems to matter since it appears he would find almost

anything modern more enjoyable than ballet's classics right now. "I danced those ballets for too many years," he says. "There are certain elements of

modern choreography classical choreography doesn't have. Modern is less mannered, more human, in a way more pedestrian, more grounded, more direct."

His fascination with modern dance dates almost from his arrival in the United States in 1974. The dances he saw by Taylor, Graham, Cunningham and

Trisha Brown left him intrigued and excited but also perplexed. "Merce's work took me quite a few years to decode," Mr. Baryshnikov says. "It was

like modern painting. You find elements you try to understand to get the feel of it before you fully appreciate it."

Why, then, didn't he devote himself to modern works sooner? "Everybody wanted me to dance 'Giselle,' " he says. Things had begun to change when he

first worked with Ms. Tharp on "Push Comes to Shove" in 1976. "She showed me that I can do something with what I learned over there," he says,

referring to Leningrad. "She showed me I can do something else, not just necessarily existing pieces, with my technical abilities. That was a

lucky meeting, lucky relationship."

MR. BARYSHNIKOV CHOOSES the work he dances with care. His injuries, which resulted in three knee operations, have limited his options somewhat,

in both modern and ballet. "There are certain things I cannot do, and certain things I can do 100 percent, but I've been working with this for

many years," he says. Nor does he believe his classical training has hindered him much in his efforts with most modern works. "Some styles, probably,

would take much longer for me to get," he says. "Certain styles may be just too late for me, at my age to spend many months to learn."

He bristles at the notion that age and injuries are behind his leap from classical ballet to modern dance. "That's utter nonsense," he scoffs. "I

could have continued with classical ballet until I wanted to stop. There are certain roles I wouldn't try. But 'Giselle,' 'Sleeping Beauty' and

certain productions of 'Romeo and Juliet,' I could have done all these years, and maybe even tomorrow. But I wouldn't get any inspiration to do

the work. It would be disaster for me. I do now much more difficult stuff -- it just may not look that way -- in pieces by Twyla and Jerry than

the whole two acts of 'Giselle.' "

Does this mean Mr. Baryshnikov is disillusioned with classical ballet? He is not, he says, adding that "there are not that many great, great

choreographers emerging fully from the classics." On the other hand, there are at least six or seven modern choreographers, like Ms. Tharp and

Mr. Morris, who he believes are energizing ballet. "It's interesting that a lot of modern choreographers do work for classical companies," he says.

"Sometimes as outsiders they're at a bit of an advantage when working with companies like that. They're bringing in their own philosophy with their work."

Of his own ballet career he says simply, "I have no regrets." Still, he sounds a bit wistful looking back on his 15-month tenure with George Balanchine

and the New York City Ballet in the late 1970's. "Probably I was trying too hard in many ways to please Mr. B.," he says. "I was not relaxed enough.

And there was a lot of pressure. But at the same time it was the most fascinating time of my 20 years in the States. Just to be next to those guys,

Mr. B. and Jerry, and to see the way they work and how. Certain values shifted in my head, and I started to look at things with different eyes -- what

I like about dancing, what I don't like about dancing."

His guest appearance with City Ballet two years ago in "Duo Concertant" was immensely satisfying. "There was much less pressure," he explains. "It was

not the most obvious choice, but I knew I could do it and do it right. There are a few other things I could have done in the earlier years. Now I have

the sort of mind to execute them right, but for the body, it's a bit too late."

Back in the studio, Mr. Besserer looks on as Mr. Baryshnikov dances the new Robbins piece. "Watching him rehearse is almost more interesting when he

has a little injury, like he has right now," Mr. Besserer says. "He goes deeper in a dramatic way. He has so much technique at his hands, he can drive

his way into a piece."

For now, at least, nearly every aspect of the White Oak Project seems to please Mr. Baryshnikov. He talks of camaraderie with his dancers and of the sweet

thrill of performing something new. He also talks about the chase, pursuing choreographers he longs to work with. "When it's not a close friend, you have

to hustle a bit," he says. "You have to remind the choreographer you're very much interested in working with him, that you will do whatever is necessary

to be in the piece. With this new piece from Jerry, it took me a long time to get through to him."

And he talks happily about independence. His troupe's name is a salute to Howard Gilman, owner of the Gilman Paper Company, who gave the group a lavish

practice facility on his lush, 7,500-acre White Oak wildlife preserve in Florida. But ticket sales, not grants or donations, are what keeps the White Oak

Project afloat, with Mr. Baryshnikov digging into his own pocket if a shortfall occurs. No politics, no policies. "I like being self-employed," he says

with a grin.

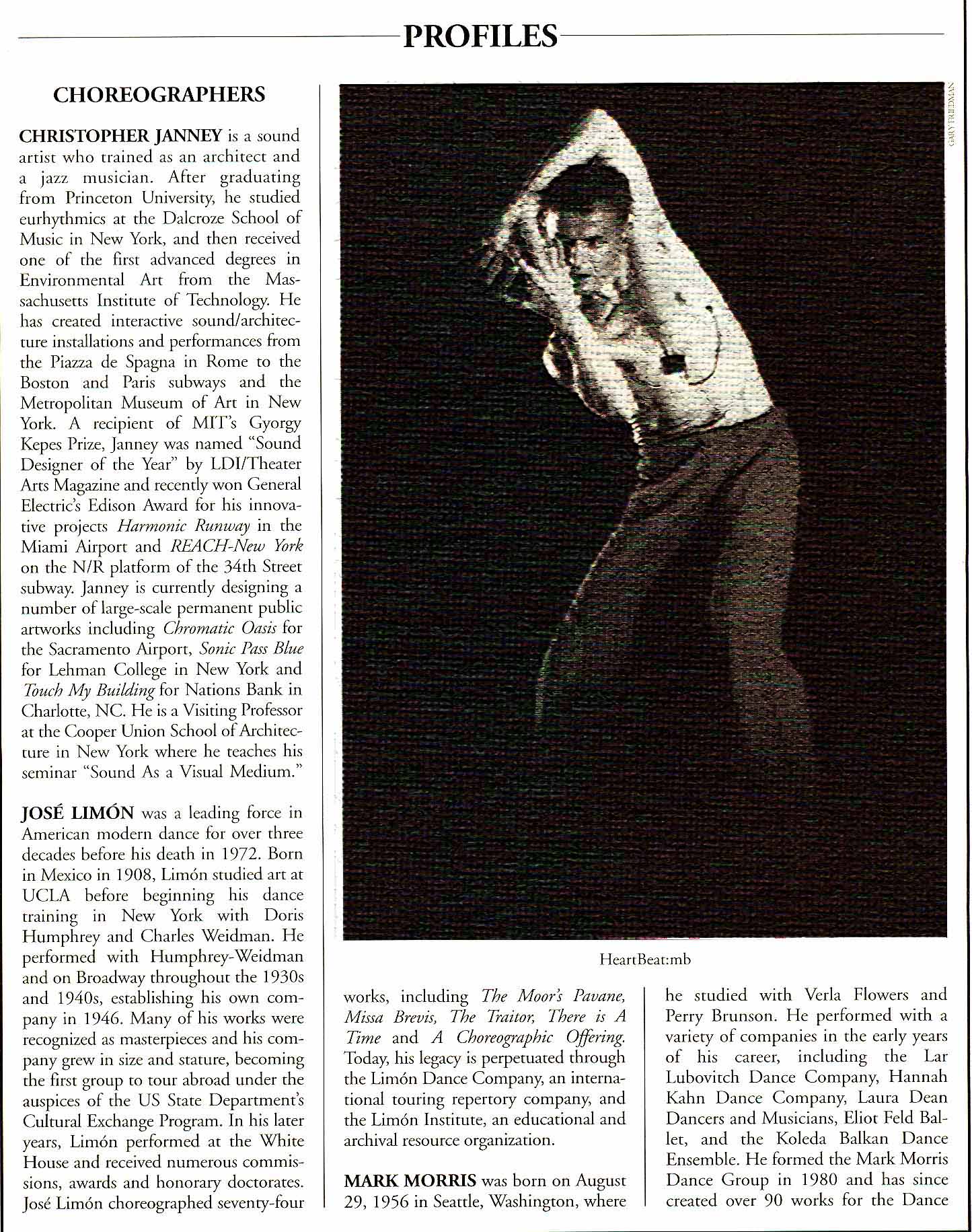

Star Syndrome Stunts White Oak Project

Mikhail Baryshnikov's presence overshadows company

June 5, 1995 / by April Austin

Staff writer of The Christian Science Monitor (Boston)

It's a pity that the White Oak Dance Project, started in 1990 by Mikhail Baryshnikov and choreographer Mark Morris,

is mainly thought of as a showcase for the mid-career Baryshnikov.

The dancer electrified audiences after his 1974 defection from the Soviet Union with his work in two great American ballet companies.

Since the creation of White Oak, he has obviously put great effort into making a democratic dance company on the order of Morris's own.

That he is having as little success as Russian President Boris Yeltsin in moving away from old systems is only partially his fault.

The project, named after the White Oak Plantation belonging to a wealthy Florida patron, has a wonderful premise. Instead of turning mature dancers

out to pasture in their 30s and 40s, why not build on their life experience and changing bodies? The project was to be collaborative and to draw on

dancers from some of the best modern companies. The dances were to be culled from brand-name choreographers like Twyla Tharp and Merce Cunningham,

with some experimental stuff thrown in.

I did not see the group's earlier work, but I understand that audiences initially felt cheated because they didn't see enough of Baryshnikov.

People who had missed him on the stages of American Ballet Theatre or the New York City Ballet wanted to take home memories of a dance legend.

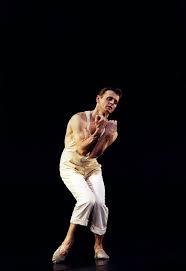

At a recent Boston performance, part of the Bank of Boston's aptly named Celebrity Series, the audience hung on Baryshnikov's every step in the solo

"Pergolesi,"

choreographed for him by Tharp. He held onlookers completely enthralled with every low, controlled jump and turn, and they gasped and applauded.

There's nothing wrong with the adulation showered on Baryshnikov, but in "Pergolesi" he crossed over the line from confidence to narcissism. He hot-dogged

his way through the charmingly puckish choreography, a knight in white satin. Tharp, in her 1992 autobiography, "Push Comes to Shove," remarked that she

learned two things about "Misha" when she first made dances for and with him in 1976: One, that he was "unbelievably eager for new movement," and two,

"his concentration span was practically nil."

With "Pergolesi," which anchored the middle part of the Boston program, Tharp indulges Baryshnikov's fantasy of being a Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly.

But it's hard to picture Astaire and Kelly patronizing an audience by directing its applause in the manner he did.

Perhaps Tharp was parodying the Russian star's Adonis-like status and mocking his vanity. She throws in sly references to classic ballets he has danced

triumphantly in the past. One could only wish that Baryshnikov had displayed his gifts with a little more humility. He may have been simply obliging his

fans. But his star turn, despite the masterly way in which he performed it, detracts from the powerful ensemble feeling generated by the other dancers.

The audience, for its part, was ecstatic.

Applause was also generous for the star's fellow dancers, who performed with polish, precision, and complete professionalism. The evening's real delight

was "Jocose," by pioneering choreographer Hanya Holm. It was danced to Maurice Ravel's "Sonata for Violin and Piano," performed live by Larry Shapiro and

Michael Boriskin. "Jocose" contains no wasted choreography. Its high energy and constantly changing patterns keep viewers from looking away even for a moment,

for fear of missing something. As it careens through swingy, waltzy, spinning movements, the dancers' personalities begin to emerge. Eventually the music

takes a turn into honkytonk, and they become like pieces of well-oiled machinery, all pulsing gears and thumping pistons. In one unusual move, the performers

bump along the floor as if bounced by an earth tremor.

Another crowd-pleaser was "Chickens," a rare opportunity to see serious dancers make flapping, crooning goofballs of themselves and love it. The only accompaniment

to Charles Moulton's choreography was a recorded monologue by David Cale, a simple tale about embracing diversity.

The dancers, Keith Sabado in particular, slipped in and out of moods and styles with chameleon grace - and quiet skill.

![]()