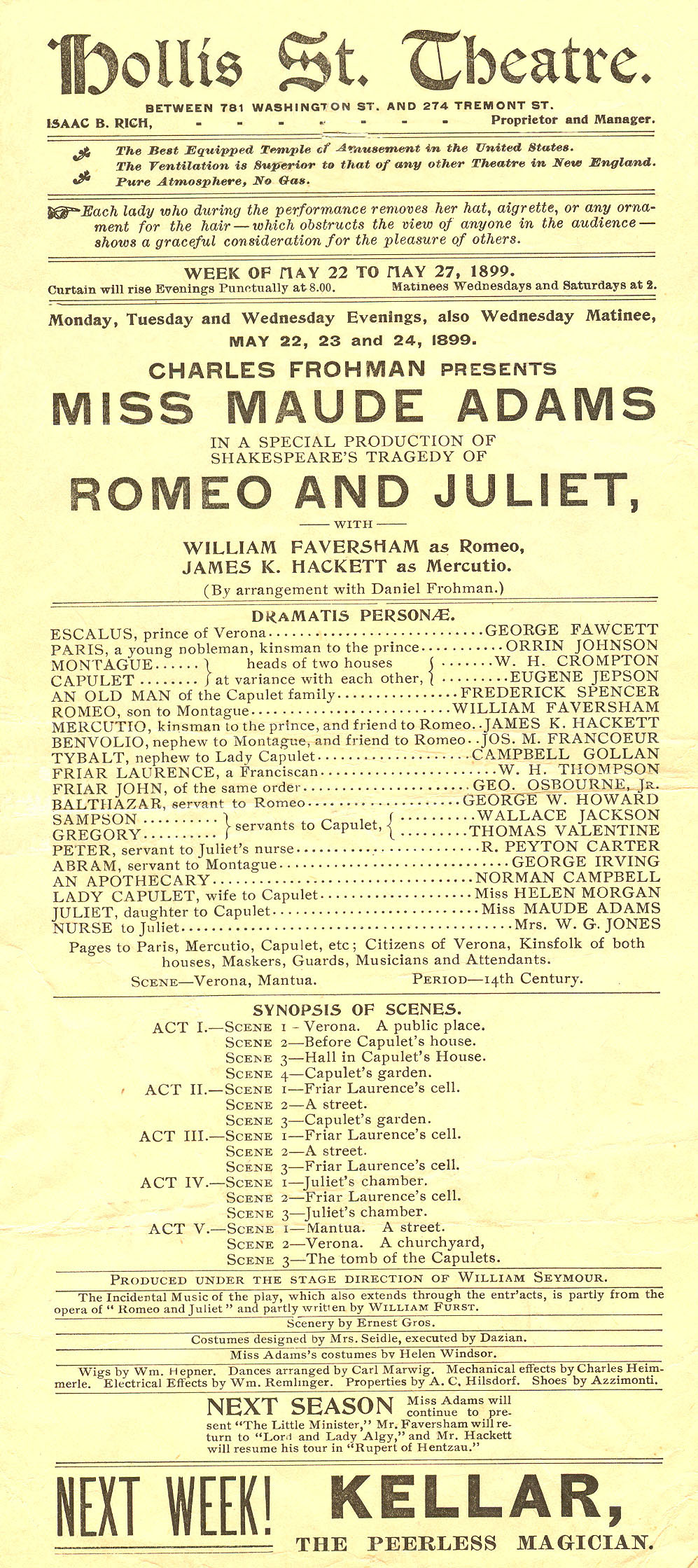

From the Acton Davies book:

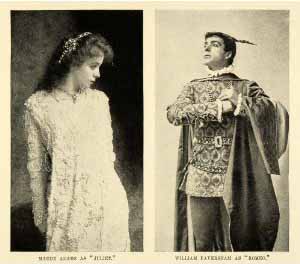

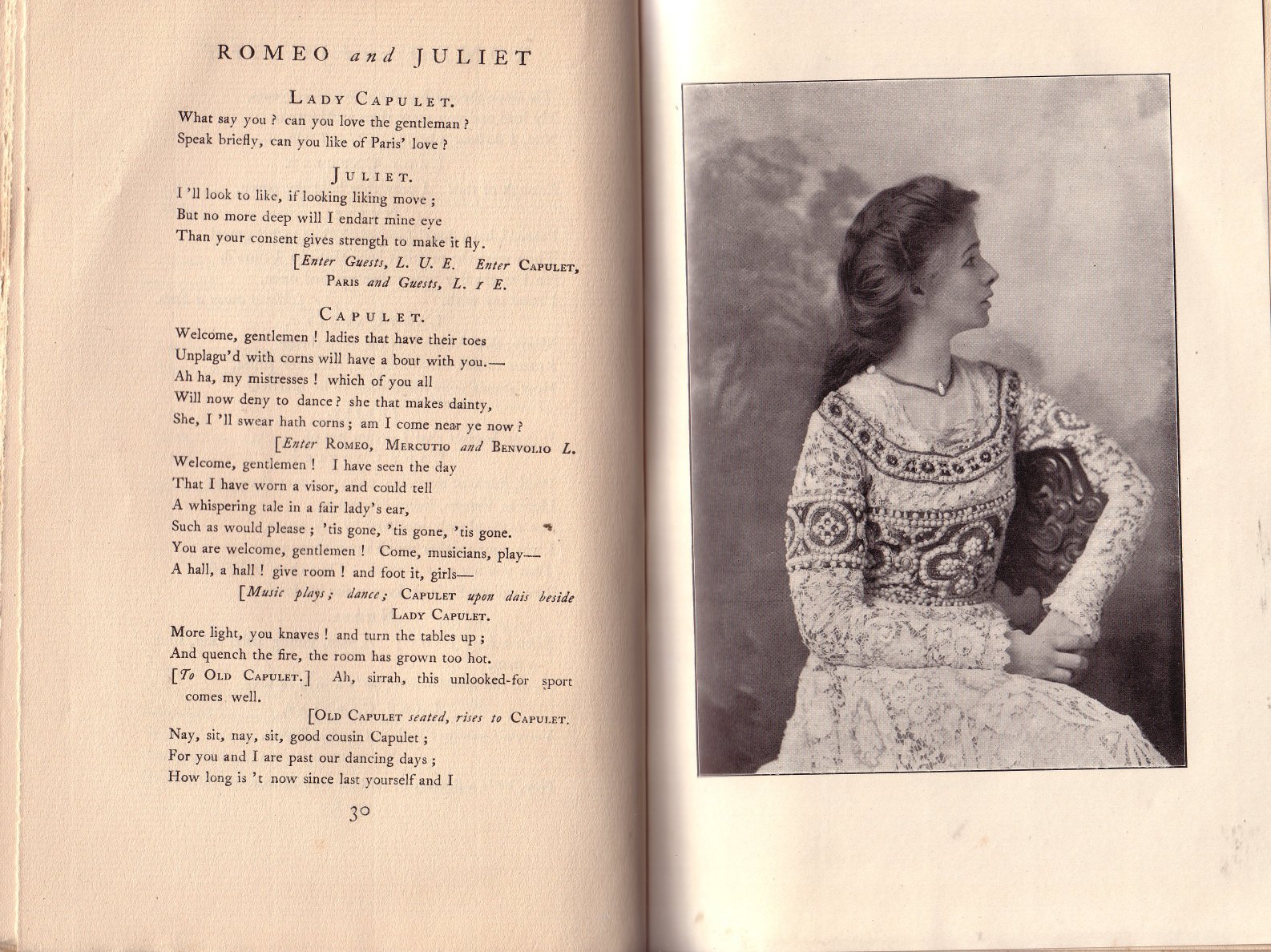

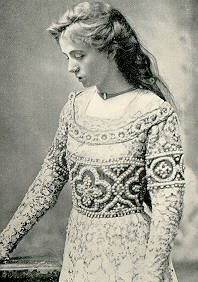

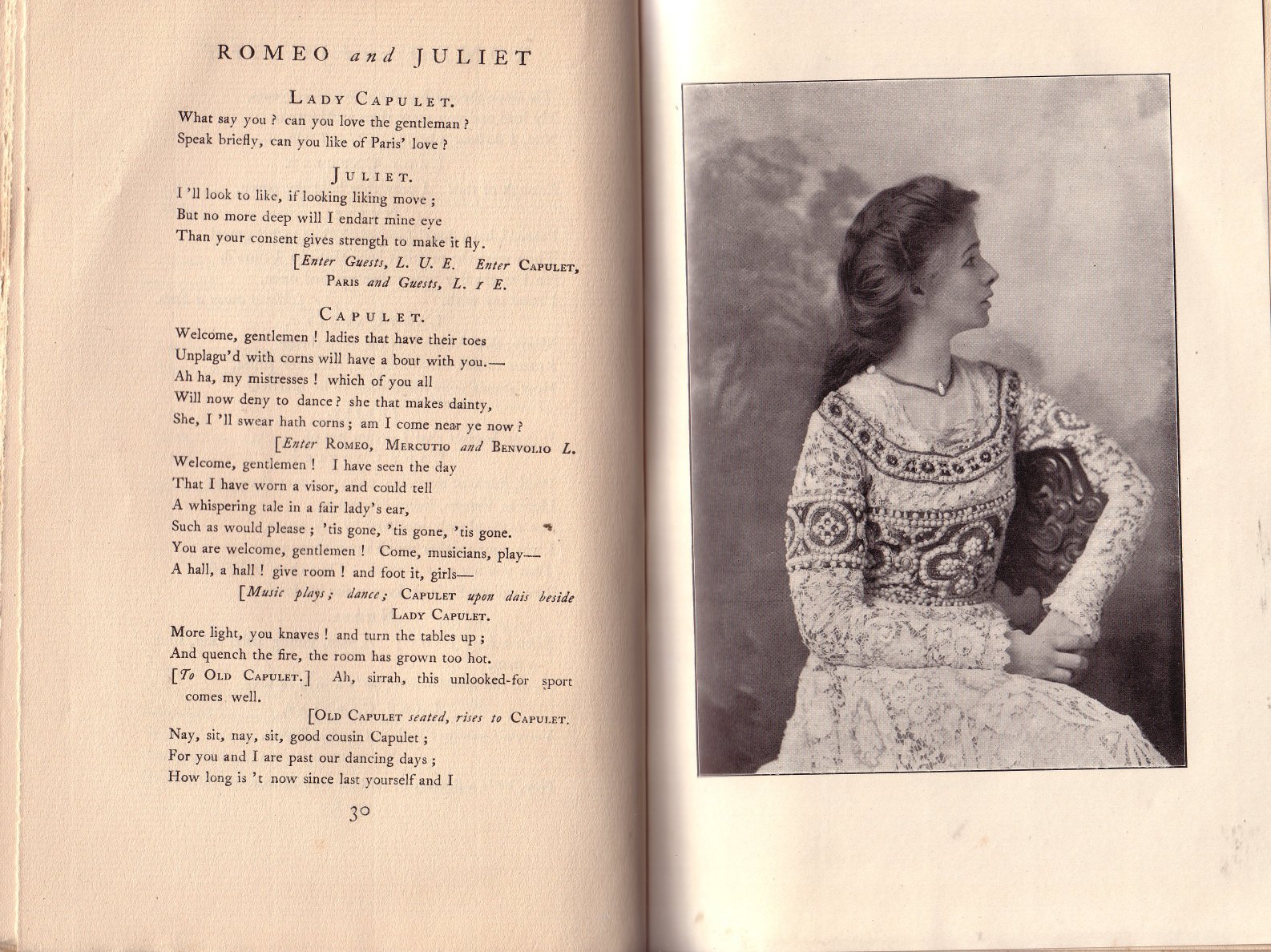

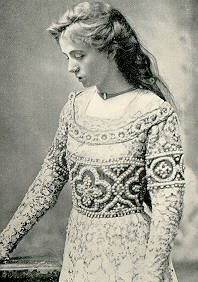

"By the end of the second season of The Little Minister she had mastered the role of Juliet, and Mr. Frohman decided to engage a special company and produce Romeo and Juliet in all the leading cities during the month of May. Mr. William Faversham played Romeo., Mr. J. K. Hackett Mercutio, while that sterling old-time actress, Mrs. D. G. Jones., gave a superb peadams/julietance of the Nurse. The opening peadams/julietance took place at the Empire early in May. The house was crowded, the enthusiasm intense, and, all things considered, Miss Adams emerged from the ordeal far more successfully than any of her best friends imagined that she would. She was wise enough to realize that for her to attempt to play Juliet in the traditional manner would be absolutely suicidal, so she threw traditions to the winds and made Juliet a simple, girlish creature of infinite charm. It was the master-stroke of a very clever woman, - an actress who knew her own artistic shortcomings too well to expose them. As a literal matter of fact, her personation of Juliet made some of the love scenes take on a new significance, for many, that they had never had before; it was a treat in itself to see a genuinely young Juliet, in the first place ; as a general rule the average actress never attempts the role until she has arrived at those years of professional experience where she is transiently forty, or at least permanently twenty-nine. The youthful charm of Miss Adams' Juliet, in short, made many champions for her, but her lack of elocutionary training damned her with the more punctilious of the old-school critics. In New York she was treated with far more consideration than in other cities. The experiment was a great financial success, however, and the following September Miss Adams returned to the treadmill with all the more zest for her temporary excursion into Shakespeare."

From Matinee Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Our Theater by Ward Morehouse:

"...the fragile and girlish Maude Adams turned from The Little Minister to Romeo and Juliet...

And the same publication (Dramatic Mirror ) reviewing Maude Adam's Juliet of the same year- we've gone over into 1899, said:

"Every good wish was here, but yet it may be said only that Miss Adams cannot play Juliet. She spoke the Bard's words of passion but shows them not in voice, action or gesture. Even her personality ill befits the part. Her reading of Shakespeare's lines seldom rang true or certain. It was vague, almost aimless, and she suffred apparently from quite pardonable nervousness."

"Notwithstanding her defeat as Juliet, the Utah-born Maude Adams, daughter of the Kiskaddens, was making a place for herself in the theater."

From the book Barrie: The Story of a Genius by J.A. Hammerton 1929:

In the two closing years of last century the triangular friendship between him (Barrie), Maude Adams and Frohman was steadily strengthening. Frohman's frequent trips to London (he was called To-and Frohman) provided the opportunities for personal contact, as the manager was the worst of correspondents, limiting himself to a sentence or two in his letters, but with Miss Adams the dramatist had to keep in touch by letter, and when in the summer of 1899 Frohman, for lack of a new play by Barrie, starred' her in Romeo and Juliet she received a whimsical epistle from Barrie asking, "Are you going to take Willie Shakespeare by the arm and l'ave me?"

By all accounts she did extremely well with Shakespeare, but she was all eagerness to take Jamie Barrie by the arm just as soon as he showed the necessary coming on disposition, and that, as it happened, was not for another eighteen months.

From the book: Charles Frohman:" Manager and Man by Issac F. Marcosson and Daniel Frohman with an Appreciation by James M. Barrie. 1916):

"Maude Adams was now launched as a profitable and successful star. Like many other conscientious and idealistic interpreters of the drama, she had a great reverence for Shakespeare, and she burned with a desire to play in one of the great bard's plays. Charles Frohman knew this. Then, as always, one of his supreme ambitions in life was to gratify her every wish; so he announced that he would present her in a special all-star production of Romeo and Juliet.

Charles Frohman himself was always frank enough to say that he had no great desire to produce Shakespeare. He lived in the dramatic activities of his day. It was shortly before this time that his brother Daniel, entering his office one day, found him reading.

"I am reading a New book," he said; "that is, New to me."

"What is that?" was the query?

Romeo and Juliet," he replied.

When Maude Adams dropped the role of Babbie to assume that of Juliet some people thought the transfer a daring one, to say the least. Even Miss Adams was a little nervous. Not so Frohman. To him Shakespeare was simply a playwright like Clyde Fitch or Augustus Thomas, with the additional advantage that he was dead, and therefore, as there were no royalties to pay, he could put the money into the production.

When Frohman went to rehearsal one day he noticed that the company seemed a trifle nervous.

"What's up?" he asked, abruptly.

Some one told him that the players were fearful lest all the details of the costume and play should not be carried out in strict accordance with history.

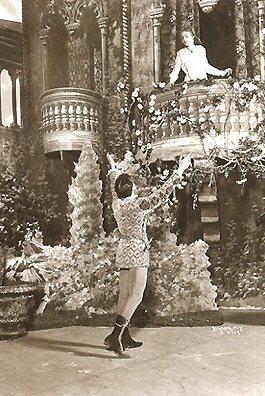

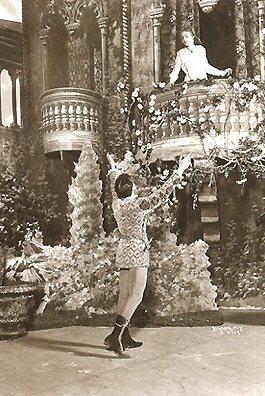

"Nonsense!" Exclaimed Frohman. "Who's Shakespeare? He was just a man. He won't hurt you. I don't see any Shakespeare. Just imagine you're looking at a soldier, home from the Cuban war, making love to a giggling school-girl on a balcony. That's all I see, and that's the way I want it played. Dismiss all idea of costume. Be modern."

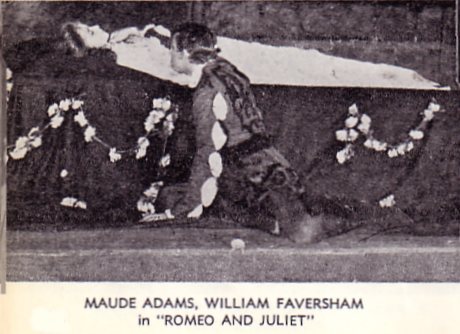

The production of Romeo and Juliet was supervised by William Seyomour. It was rehearsed in two sections. One half of the cast was in New York, with Faversham and Hackett; the other was on tour with Miss Adams in The Little Minister. Seymour divided his time between the two wings, with the omnipresent spirit of Frohman over it all.

Miss Adams had made an exhaustive study of the part. After his first conference with her, Seymour wrote to Frohman as follows:

"I thought I knew my Shakespeare, but Miss Adams has opened up a new and most wonderful field. An hour with her has given me more inspiration and ideas than twenty years of personal experience with it."

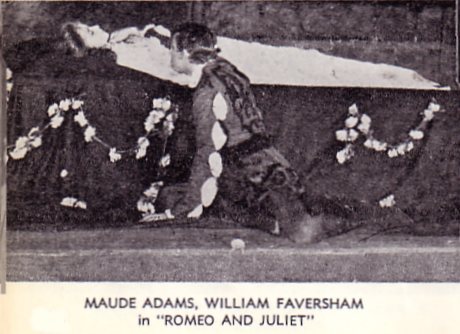

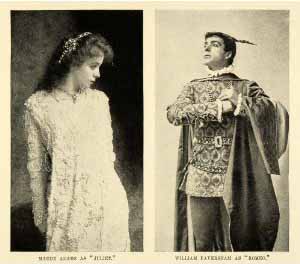

As usual, Frohman surrounded Miss Adams with a magnificent cast. William Faversham played Romeo; James K. Hackett was Merucutio; W.H. Thompson was Friar Lawrence; Orrin Johnson played Paris; R. Peyton Carter was Peter. Others in the company were Campbell Gollan and Eugene Jepson.

Romeo and Juliet was produced at the Empire Theater May 8, 1899, and was a distinguished artistic success. Miss Adams's Juliet was appealing, romantic, lovely. It touched the chords of all her gentle womanliness and gave the character, so far as the American stage was concerned, a new tradition of youthful charm.

A unique feature of the first night's performance of Romeo and Juliet was the presence of Mary Anderson. This distinguished actress, who had just arrived from London for a brief visit, expressed a desire to see the New Juliet, and to feel once more the thrill of a Broadway fist night. Miss Anderson herself had, of course, achieved great distinction as Juliet. She was regarded, in her day, as the physical and romantic ideal of the role.

When her desire to see the play was communicated to Charles, it was found that every box had been sold except the one reserved for his sisters. He therefore purchased this from them with a check for $200.

At the conclusion of the performance Miss Anderson was introduced to Miss Adams, and congratulated her on her success.

From the book Hear the Distant Applause! Six Great Ladies of the American Theatre by Marguerite Vance, 1963:

During the long run of The Little Minister, Mr. Frohman thought to relive the monotony for the cast by producing Romeo and Juliet. Maude must have smiled a little smile of frustration when she heard his plan. She had always wanted to play tragedy. it seemed so much more romantic to her young imagination, and in the last decade of the nineteenth century, at least among conservative theatergoers, comedy was considered not in quite as good taste as the tragic or classical drama. Once her mother had warned her sensibly: "Child, look at your profile in the mirror. With a turned-up nose like that, how can you expect to play tragedy?"

Well, one cannot be blamed for hoping, and with such a variety of comedies already to her credit Maude Adams never quite abandoned the hope that one day she would be asked to act in a tragedy and so prove her versatility. Romeo and Juliet seemed the perfect answer. Then came the blow; Mr. Frohman did not want a tragic Juliet! One might as well demand that rivers run uphill! But Maude Adams demonstrated the full scope of her ability; she gave Mr. Frohman exactly the Juliet he wanted-gay, artless, ingenuous, yet capable of profound depths of feeling.

When the play opened in New York in may 1909, the critics were largely complimentary. one ended his lengthy review with this final paragraph: "It is finely emotional and intensely appealing on its tragic side, although the element of deep pathos is substituted for moving force. It is the Juliet of a comedienne equipped with wonderful range of power.

In Boston, where it played next, a critic said: "The stage has waited for Miss Adams to give to Juliet a sense of humor-and yet there is plenty of warrant for it in the text. It met with critical appreciation.

Some of the critics were caustic, tongue-in-cheek, sarcastic. Said the most influential of them all, William Winter: "Many schoolgirls with little practice would play the part just as well-and would be just as like it...Much of the part was whispered and much of it as bleated. The personality cannot readily be described, but perhaps it may not be unfairly indicated as that of an intellectual young lady from Boston, competent in the mathematics and intent on teaching pedagogy." This must have been bitter criticism to take, and reading it Maude Adams must have decided then and there that tragedy was not for her.

Reviews

The play opened on May 8th, 1899. One critic wrote:

"Miss Adam's Juliet is a triumph in the impersonation of simple, spontaneous, unaffected girlhood. it is rich in romantic charm and great viewed from the standpoint of comedy."

"It is finely emotional and intensely appealing on its tragic side, although the element of deep pathos is substituted for moving force. It is the Juliet of a comedienne equipped with wonderful range of power."

A critic in Boston wrote:

"The Juliet of Maude Adams proved to be a Juliet worthy of close, critical attention. It was absolutely new."

"If Miss Adams were judged by the same standard which was applied to the long line of famous Juliets who have occupied public attention during the past thirty years the result would be a stupendous compilation of condemnatory phrases, and yet to us this new Juliet is the most girlish, the most tender, the most lovable, the most sympathetic, the most human and the most convincing we have ever seen."

"The stage has waited for Miss Adams to give to Juliet a sense of humor-and yet there is plenty of warrant for it in the text. It met with critical appreciation..."

William Winter of the Tribune wrote a critical review:

"Miss Adams, a delicate, seemingly fragile and febrile person, in the potion scene of Juliet might be expected to supply a mild specimen of hysterics. That was feasible. and that was afforded. The individual charm of girl-like sincerity which is peculiar to Miss Adams swayed her peadams/julietance of Juliet with a winning softness, eliciting sympathy and inspiring kindness. Beyond that there was nothing. Many schoolgirls, with a little practice, would play the part just as well-and would be just as little like it. In her special way Miss Adams is a most agreeable actress; she ought to be neither surprised nor hurt to ascertain by this experience that nature never intended her to act the tragic heroines of Shakespeare. Much of the part was whispered and much of it was bleated. The personality cannot readily be described, but perhaps it may not be unfairly indicated as that of an intellectual young lady from Boston, competent in the mathematics and intent on teaching pedagogy. A balcony scene without passion, a parting scene without delirium of grief, and a potion scene without power-those were the products of Miss Adam's dramatic art."

A writer from the Philadelphia Item wrote a very interesting sort of rebuttal to the above review:

"The first night of Miss Adam's appearance as Juliet did not end in the theater until after eleven l1 o'clock; yet, the country edition of the Tribune of the following day contained a long critique in denunciation of the evening's proceedings...One of the metropolitan journals of yesterday made the declaration that copies of Mr. Winter's critique were at 11:30 o'clock in the hands of out-of-town correspondents...and the same article adds that Mr. Winter had not left the theatre at 11:30. The subject and the theory are not new; and Mr. Winter's apparent speed with the pen has been a matter of comment in the past."

And yet another critic's review: "the best Juliet I have ever seen, and I have seen many of them. It shows deep study; much feeling and fire that only youth can bring. There is no artificiality about her.A wistful, elusive quality."

Curiosity and surmise are rife as to Miss Adam's Juliet. One thing may be depended upon. We shall not see a conventinoal performance. The personality and art of this actress are never violent. Her Juliet will remain a gentle girl, and not become a tragedy queen. So a positive novelty, at least, is in store for us.” (Sun, May 7, 1899)

Capitalizing on her natural appearance and personality, she emphasized Juliet's youth and girlishness. She utilized a natural style in speech and movement, eliminating all traces of declamation, self-conscious elocution, and posturing.” (Maude Adams, an American Idol: True Womanhood Triumphant in the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Century Theatre, doctoral thesis, 1984, Eileen Karen Kuehnl)

It was far better in a realization of the girlishness and emotionality of Shakespeare's heroine than in a perfect rendering of his lines. Anyone who looked for an interpretation of the beautiful speeches the author puts into Juliet's mouth would be disappointed; another, who sought only the imperssions of a very young and emotional girl carried through a tragic romance, would find in Miss Adam's portrayal a most moving and convincing picture. In appearance she is not at all the warm and precocious beauty of a Southern clime,but what she lacks in Italian seriousness she makes up in vivacity and a magnetism peculiarly her own. Miss Adams can never be a great Juliet, but she may always be a charming one.” (Life, May 18, 1899)

Miss Adam's Juliet is a triumph in the impersonation of simple, spontaneous, unaffected girlhood. It is rich in romantic charm and great viewed from the standpoint of comedy.” The World, May 9, 1899

Her portrayal of Juliet is sensibly and sympathetically conceived and executed with beautiful sincerity and simplicity. it is lovely in spirit, absolutely free from affectation and extravagance, fervent and affecting, and sustained from first to last by a natural eloquence of speech, gesture, and facial play which will more than atone, in the minds of some hundreds of thousands of spectators in the years to come, for her lack of mere elocutionary power and studied plastic grace.” (New York Times, May 9, 1899)

Title of review: "Sad Affair at the Empire”:

“Miss Adams, a delicate, seemingly fragile and febrile person, in the potion scene of Juliet, might be expected to supply a mild specimen of hysterics. That was feasible, and that was afforded. The individual charm of girl-like sincerity which is peculiar to Miss Adams swayed her performance of Juliet with a winning softness, eliciting sympathy and inspiring kindness. Beyond that there was nothing. Many schoolgirls, with a little practice, would play the part just as well and would be just as little like it. In her special way Miss Adams is a most agreeable actress; she outght to be neither surprised nor hurt to ascertain by this experience that nature never intended her to act the tragic heroines of Shakespeare. Much of the part ws whispered and much of it was bleated. The personality cannot readily be descried, but perhaps it will not be unfairly indicated as that of an intellectual young lady from Boston, competent in the mathematics and intent on teaching pedagogy. A balcony scene without passion, a parting scene without the delirium of grief, and a potion scene without power-those were the products of Miss Adam's dramatic art.” (Tribune, May 9, 1899)

It is quite likely that the Juliet of this fortunate young lady may find many warm admirers...But it is removed by many degrees from all commonly received ideals of the Juliet of Shakespeare, and it cannot be admitted that the originality of the treatment is sufficient compensation for its many obvious shortcomings.” (Evening Post, May 9, 1899)

The greatest charm of Miss Adam's experiment with Juliet, for me, lay in the effect of sincerity she secured by this natural and smiple manner in stirring passages like the 'O, bit me leap,' in which, while not approaching any accepted ideas of tragic expression, she yet made the listener feel the pity and horror of the situation.” (New York Times, Jan. 14, 1900)

The recalls to which she responded were many, and she might have doubled their number if she had chosen to turn all the applause to account in that way. her conduct in that respect was modest. She came out in every instance with one or more of her companion players, and accepted in an apologetic manner the honors paid to her. (New York Sun, May 9, 1899)

Reference: Bookmice

- Actual program (broadside) measures 5 1/2 "x 12")

![]()