The Iroquois Theatre (Chicago) tragedy

It was a chilly Wednesday, December 30th, 1903. Downtown Chicago had been hit squarely with the icy fist of winter. People hurried about their day, filled with dreams and hopes of what the coming year would bring. The past year had been plagued with numerous strikes, economic depression, and ever-increasing crime. Children were out of school for the holidays and looking forward to an enjoyable matinee performance at the newest theatre in town, The Iroquois Theatre. In fact, the six-story tall Iroquois had only been open for five-weeks and was described as a magnificent palace of marble and mahogany, a "virtual temple of beauty", and had been advertised as "absolutely fireproof". The theater was equipped with an asbestos curtain, which could be lowered to separate the audience from any fire on stage.

Located on 24-28 W. Randolph Street, between State and Dearborn, the theater could seat 1,724 customers. But today's matinee, 1,900 people filled the theater to 'standing room only' capacity to see vaudeville comedian Eddie Foy, Annabelle Whitford and a performance troupe of 500, in the musical comedy, "Mr. Bluebeard". Foy, ridiculously dressed in drag, kept the audience laughing happily through the frolicking first act. After a short intermission, Joseph Dillea's pit orchestra struck up the first bars of a tune called "In the Pale Moonlight" as the second act started about 3:15pm with the chorus on stage, singing and dancing.

Out of sight, suspended by ropes high above the stage, were thousands of square feet of painted canvas scenery flats. On a catwalk, amid the scenery, stagehand William McMullen saw a bit of the canvas brush against a hot reflector behind a calcium arc spotlight. A tiny flame erupted. McMullen tried to crush it out with his hand but it was two inches beyond his reach.

Quickly the fire spread. The on-duty fireman tried desperately to stop the blaze, but was only equipped with two tubes of a patent powder called Kilfyres, which was completely ineffective on the fire. Foy had just walked onstage when an overhead light shorted and sparked, splashing rivulets of fire onto a velvet curtain and flammable props.

When a bit of burning scenery fell among the singers, they fled from the stage in a rush. The orchestra played on as Foy ran to the footlights and tried to calm the crowd. "Everything is under control," he said just as a mass of burning debris fell at his feet. He shouted to the stage manager to drop the theater's asbestos curtain. To his horror, the protective curtain snagged a projecting light fixture and jammed in its wooden tracks. The frightened singers and dancers, waiting backstage, fled from the stage door at the rear of the theater. That singular act sealed the Iroquois' doom. The sudden draft of icy air rushed in through the open door, billowing the flames under the partially-lowered asbestos curtain. The fireball reached over the heads of those on the first floor like the arm of a demon, spanning the 50-foot gap to the balconies. Everything combustible ignited instantly. With one accord, the audience made a rush to the doors.

"A sort of cyclone came from behind," Foy reported. "And there seemed to be an explosion." As the stage started collapsing, the

audience bolted for the twenty-seven exits, only to find many of them with iron gates covering them. Some of the gates were locked,

while others were unlocked but opening them required operation of a small lever of a type unfamiliar to most theater patrons. Other

doors opened inwards. Those in front were trampled and crushed against the doors by the onrush of humanity.

In darkness, the living clawed over bodies piled 10 high around doors and windows, especially in the stairwell area exits from the balcony to the main floor. Other fatalities occurred as fire broke out underneath an alley fire escape, causing people above the fire to jump. The first to jump died as they hit the hard pavement. Later jumpers landed on the bodies and survived. Patrons also jumped from the balcony to the main floor of the theater with the same effect. Within fifteen minutes, it was all over. By the time firefighters arrived, the auditorium was silent. Firemen snuffed out the blaze within half an hour, but hope did not survive.

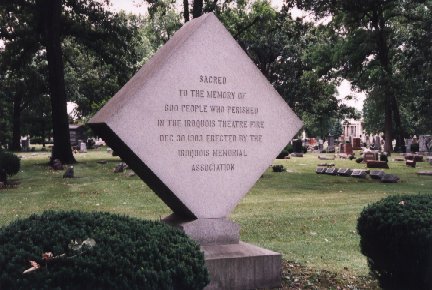

Five hundred and seventy five were dead; at least 27 more would die from their injuries. Families were devastated and torn apart, women and children suffering the most. Among the 500 performers and backstage personnel, only the tightrope artist caught high above the stage died. A temporary morgue was set up nearby to allow friends and relatives to identify the victims. Many of the victims were buried in Montrose, Forest Home and Graceland cemeteries in Chicago.

The Iroquois fire, with 602 casualties, was the deadliest blaze in Chicago history, second in the United States and fourth worldwide.

In the United States, the disaster was unmatched even by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which killed 250, or the 1942 Coconut

Grove night club blaze in Boston, which claimed 490 lives.

A coroner's inquest began within a week. Over two hundred witnesses testified. It was a national sensation, exposing unbelievable laxity on the part of the theater and city officials charged with public safety. Hearings revealed that 'complimentary' tickets motivated city inspectors to ignore the fire code and let the theater open. Theater principals, building owners, Chicago Mayor Carter H. Harrison and others were indicted, but those cases eventually were dismissed on technicalities. The only person to serve a jail term was a tavern keeper whose nearby saloon was used as a temporary morgue. He was convicted of robbing the dead.

Not one of the injured survivors or victims' relatives ever collected a cent of damages.

Mayor Harrison shut down 170 theaters, halls and churches for a months-long re-inspection that left 6,000 people unemployed. Under the new laws, the fire code was changed to require theater doors to open outwards, to have exits clearly marked and fire curtains made of steel. Also, theater management were now required to practice fire drills with ushers and theater personnel.

The Iroquois, which sustained only light interior damage, was repaired and reopened less than a year later as the Colonial Theater. In 1926, it was torn down to make way for the Oriental Theatre.